Many foreigners who have spent time in China feel compelled to write a memoir about their experiences in this big, mysterious country. Unfortunately many of these books turn out not to be especially entertaining or interesting. Just because you've lived in China, it doesn't mean you have either good writing skills or anything insightful to say about the place. Every now and again though, a book comes out which really manages to capture the essence of the foreign experience in China. Here are a few of the best ones I have read so far.

River Town, by Peter Hessler

This classic remains the standard for the "foreigner in China" genre. In 1997 young American literature graduate Peter Hessler ends up on a two year stint teaching english in Fuling, a small town near Chongqing, in the proverbial middle of nowhere. New to China and not knowing a word of Chinese, he has to figure everything out for himself. His book is a superbly crafted description of his experiences, and what he comes to understand about China and his own culture in the process.

The book doesn't gloss over some of the less savoury aspects of the society which Hessler finds himself immersed in, but he always does his best to find poetry and beauty where he can. Hessler's students, young adults from the Sichuanese countryside training to be teachers, really come alive in his description. The challenges and the fun of teaching English literature in the middle of China are also described quite vividly.

After writing this book Hessler moved to Beijing, where he wrote another two books about China and became well known for his ability to describe the country to American audiences. He has now moved to Cairo, where he is trying to learn Arabic and write about the Middle East.

Mr. China, by Tim Clissold

A memoir by Tim Clissold, an englishman who set up shop in Beijing in the early nineties as a young, starry-eyed businessman with dreams of making it big in China's new market economy.

After a year of studying Chinese in Beijing, Tim was hired by a Wall Street banker referred to only as "Pat" (in actuality Jack Perkowski), who needed someone to oversee how the millions of dollars he was pouring into Chinese factories were being put to use. Inevitably all sorts of unforseen problems arose, from factory bosses escaping to Las Vegas with 58 million in cash, to other bosses transferring land to rival factories personally owned by their associates. Tim had to run around China from one end to the other, trying to deal with all the mishaps and explain them to incomprehending American investors.

The book is certainly entertaining, and does its best to be culturally sensitive. At the same time, it reads a bit like an expose' of the kind of business ventures which unprepared, amateurish Westerners would throw themselves into in the China of the nineties. Apparently Jack Perkowski now blames Tim Clissold for many of the problems the book describes, and has refused to read it. Perhaps he should have thought it through before hiring a clueless young man with one year's experience in China to oversee 418,000,000 dollars in investment?

The Forbidden Door (La Porta Proibita), by Tiziano Terzani

Tiziano Terzani was an Italian writer, journalist and adventurer who spent decades living all across Asia. He was well known in Italy for his deep knowledge of Asian languages and cultures, and for his fascinating travel books.

The book he wrote on his years in China (called La porta Proibita in Italian) is a fascinating portrayal of the country in the early eighties: in some ways so different from now, and in some ways exactly the same. It also offers something different from the Anglo-Saxon perspective of many foreign authors who have written about China. Although Terzani was enthralled by Maoism as a young man, he became highly critical of the Chinese system after moving there. At the same time he discovered the real, human side of China, which he found much more interesting and exciting than the faultless facade which the authorities attempted to show the outside world.

Unfortunately Terzani died of cancer in 2004, after spending his last few months in the hills of his native Tuscany. No other Italian has since written about China as insightfully as he did.

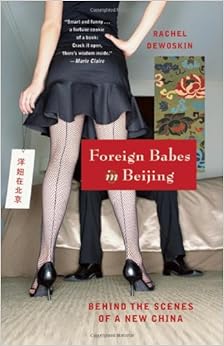

Foreign Babes in Beijing, by Rachel DeWoskin

Rachel DeWoskin, the daughter of an American Sinologist, arrived in Beijing in 1994, aged 23, to work in an American PR firm. Before long Rachel, who had no acting experience and shaky Chinese, was offered the starring part in a TV soap on a foreign lady who falls in love with a Chinese man. The show was hugely successful, gaining over 600 million viewers, and Rachel turned into a celebrity and a sex symbol overnight.

Rachel DeWoskin, the daughter of an American Sinologist, arrived in Beijing in 1994, aged 23, to work in an American PR firm. Before long Rachel, who had no acting experience and shaky Chinese, was offered the starring part in a TV soap on a foreign lady who falls in love with a Chinese man. The show was hugely successful, gaining over 600 million viewers, and Rachel turned into a celebrity and a sex symbol overnight.

Her memoir is a sensitive, amusing description of her five years in the Chinese capital, during which Rachel delved into the city's emerging alternative arts and rock music scene and met all sorts of curious characters, while holding down a variety of jobs. China was an exciting and bewildering place to be at the time, and Rachel always did her best to keep an open mind on what she experienced.

The book is a great portrayal of what expat life was like in Beijing in the nineties, a time when you could receive an offer to appear on TV just for having a foreign face and being able to put three words of Chinese together, everyone was curious about Westerners and their culture, foreigners were only allowed to live in certain neighbourhoods but would happily flout the law, and the traffic and pollution were still at bearable levels.

Why China will Never Rule the World, by Troy Parfitt

After a decade spent living in Taiwan as an anonymous English teacher, Canadian Troy Parfitt got fed up with hearing supposed experts back in the West go on about how China was going to become the next superpower and a dominant influence throughout the world. This just didn't chime with his experience. So armed with his ability to speak Chinese and his first-hand knowledge of Chinese culture, Parfitt decided to embark on a long journey through Mainland China and Taiwan, and craft it into a travelogue with an agenda.

The first part is a bitter and sometimes hilarious description of his travels through the Mainland, which are replete with the sort of of misadventures any old China-hand will be familiar with: revolting restrooms, rude, unresponsive or just plain idiotic staff, dismal accommodation, tacky "ancient ruins" rebuilt 20 years ago, scams and touts etc.... Parfitt finds almost nothing to like in China, and he is not afraid to say it like he sees it. His descriptions of his travels are replete with historical and cultural digressions, during which he dismisses Chinese culture and all it stands for. In the end, Parfitt concludes that China is condemned to remain authoritarian forever, and has no hope of gaining any kind of real global influence any time soon. Although he has no love for China's current rulers, he sees the roots of the problem as lying even deeper, in Confucianism and the country's basic cultural identity.

In the second part of the book, Parfitt tours his adopted homeland of Taiwan, and meanwhile tells us his impressions of Taiwanese society which he gained from his years of living there. He describes Taiwan as being a better place than the Mainland in almost every way, but he still finds Taiwanese society to be lacking in many important respects, and he blames Chinese culture and education for the lack of critical thinking, ignorance and obtuseness which he perceives all around him.

Obviously Parfitt's conclusions are highly provocative and debatable, and not everything he claims about China is true. It is not true, for instance, that you never see people exercise outdoors (has he ever been to a Chinese park?). I don't find it to be the case that nobody ever knows the way to anywhere, a constant theme throughout the book. Parfitt's historical anecdotes are interesting and informative, but often biased, and dismissing the whole of Chinese history as nothing but war and chaos is highly simplistic. At the same time, I think anyone who knows China properly will find themselves secretly agreeing with him every once in a while.

If this book deserves to be read, it is mainly because it gives vent to some of the negative attitudes and frustration which many long-term foreign residents develop towards Chinese culture. At the end of the book Parfitt describes how he decided to move back to Canada, finally fed up with Taiwan and Chinese society as a whole. This was clearly a long overdue decision.

River Town, by Peter Hessler

This classic remains the standard for the "foreigner in China" genre. In 1997 young American literature graduate Peter Hessler ends up on a two year stint teaching english in Fuling, a small town near Chongqing, in the proverbial middle of nowhere. New to China and not knowing a word of Chinese, he has to figure everything out for himself. His book is a superbly crafted description of his experiences, and what he comes to understand about China and his own culture in the process.

The book doesn't gloss over some of the less savoury aspects of the society which Hessler finds himself immersed in, but he always does his best to find poetry and beauty where he can. Hessler's students, young adults from the Sichuanese countryside training to be teachers, really come alive in his description. The challenges and the fun of teaching English literature in the middle of China are also described quite vividly.

After writing this book Hessler moved to Beijing, where he wrote another two books about China and became well known for his ability to describe the country to American audiences. He has now moved to Cairo, where he is trying to learn Arabic and write about the Middle East.

Mr. China, by Tim Clissold

A memoir by Tim Clissold, an englishman who set up shop in Beijing in the early nineties as a young, starry-eyed businessman with dreams of making it big in China's new market economy.

After a year of studying Chinese in Beijing, Tim was hired by a Wall Street banker referred to only as "Pat" (in actuality Jack Perkowski), who needed someone to oversee how the millions of dollars he was pouring into Chinese factories were being put to use. Inevitably all sorts of unforseen problems arose, from factory bosses escaping to Las Vegas with 58 million in cash, to other bosses transferring land to rival factories personally owned by their associates. Tim had to run around China from one end to the other, trying to deal with all the mishaps and explain them to incomprehending American investors.

The book is certainly entertaining, and does its best to be culturally sensitive. At the same time, it reads a bit like an expose' of the kind of business ventures which unprepared, amateurish Westerners would throw themselves into in the China of the nineties. Apparently Jack Perkowski now blames Tim Clissold for many of the problems the book describes, and has refused to read it. Perhaps he should have thought it through before hiring a clueless young man with one year's experience in China to oversee 418,000,000 dollars in investment?

The Forbidden Door (La Porta Proibita), by Tiziano Terzani

Tiziano Terzani was an Italian writer, journalist and adventurer who spent decades living all across Asia. He was well known in Italy for his deep knowledge of Asian languages and cultures, and for his fascinating travel books.

|

| Terzani and his wife eating with some Chinese friends |

Terzani

was fluent in Chinese, a language he learnt in Stanford in the late

sixties, and always curious about China. As soon as the country opened

up slightly to the outside world in the early eighties, he moved to

Beijing as a correspondent for a German magazine. Terzani arrived in the

Chinese capital in 1980, when foreigners where still extremely rare. He

immediately did his best to integrate and learn about his new home,

refusing to remain confined within the diplomatic compound where

foreigners were forced to live at the time. He rode a bike, sent his

children to a local school (which they hated), travelled around the

country hard class, and got to know as many people as possible. In the

end the authorities got fed up with this man who just wouldn't stick to

the script; in 1984, Terzani was arrested on the fabricated accusation

of smuggling artistic treasures out of the country, "re-educated" for a

month (which mainly consisted in him having to write nonsense

confessions), and then kicked out of China.

The book he wrote on his years in China (called La porta Proibita in Italian) is a fascinating portrayal of the country in the early eighties: in some ways so different from now, and in some ways exactly the same. It also offers something different from the Anglo-Saxon perspective of many foreign authors who have written about China. Although Terzani was enthralled by Maoism as a young man, he became highly critical of the Chinese system after moving there. At the same time he discovered the real, human side of China, which he found much more interesting and exciting than the faultless facade which the authorities attempted to show the outside world.

Unfortunately Terzani died of cancer in 2004, after spending his last few months in the hills of his native Tuscany. No other Italian has since written about China as insightfully as he did.

Foreign Babes in Beijing, by Rachel DeWoskin

Rachel DeWoskin, the daughter of an American Sinologist, arrived in Beijing in 1994, aged 23, to work in an American PR firm. Before long Rachel, who had no acting experience and shaky Chinese, was offered the starring part in a TV soap on a foreign lady who falls in love with a Chinese man. The show was hugely successful, gaining over 600 million viewers, and Rachel turned into a celebrity and a sex symbol overnight.

Rachel DeWoskin, the daughter of an American Sinologist, arrived in Beijing in 1994, aged 23, to work in an American PR firm. Before long Rachel, who had no acting experience and shaky Chinese, was offered the starring part in a TV soap on a foreign lady who falls in love with a Chinese man. The show was hugely successful, gaining over 600 million viewers, and Rachel turned into a celebrity and a sex symbol overnight.The book is a great portrayal of what expat life was like in Beijing in the nineties, a time when you could receive an offer to appear on TV just for having a foreign face and being able to put three words of Chinese together, everyone was curious about Westerners and their culture, foreigners were only allowed to live in certain neighbourhoods but would happily flout the law, and the traffic and pollution were still at bearable levels.

Why China will Never Rule the World, by Troy Parfitt

After a decade spent living in Taiwan as an anonymous English teacher, Canadian Troy Parfitt got fed up with hearing supposed experts back in the West go on about how China was going to become the next superpower and a dominant influence throughout the world. This just didn't chime with his experience. So armed with his ability to speak Chinese and his first-hand knowledge of Chinese culture, Parfitt decided to embark on a long journey through Mainland China and Taiwan, and craft it into a travelogue with an agenda.

The first part is a bitter and sometimes hilarious description of his travels through the Mainland, which are replete with the sort of of misadventures any old China-hand will be familiar with: revolting restrooms, rude, unresponsive or just plain idiotic staff, dismal accommodation, tacky "ancient ruins" rebuilt 20 years ago, scams and touts etc.... Parfitt finds almost nothing to like in China, and he is not afraid to say it like he sees it. His descriptions of his travels are replete with historical and cultural digressions, during which he dismisses Chinese culture and all it stands for. In the end, Parfitt concludes that China is condemned to remain authoritarian forever, and has no hope of gaining any kind of real global influence any time soon. Although he has no love for China's current rulers, he sees the roots of the problem as lying even deeper, in Confucianism and the country's basic cultural identity.

In the second part of the book, Parfitt tours his adopted homeland of Taiwan, and meanwhile tells us his impressions of Taiwanese society which he gained from his years of living there. He describes Taiwan as being a better place than the Mainland in almost every way, but he still finds Taiwanese society to be lacking in many important respects, and he blames Chinese culture and education for the lack of critical thinking, ignorance and obtuseness which he perceives all around him.

Obviously Parfitt's conclusions are highly provocative and debatable, and not everything he claims about China is true. It is not true, for instance, that you never see people exercise outdoors (has he ever been to a Chinese park?). I don't find it to be the case that nobody ever knows the way to anywhere, a constant theme throughout the book. Parfitt's historical anecdotes are interesting and informative, but often biased, and dismissing the whole of Chinese history as nothing but war and chaos is highly simplistic. At the same time, I think anyone who knows China properly will find themselves secretly agreeing with him every once in a while.

If this book deserves to be read, it is mainly because it gives vent to some of the negative attitudes and frustration which many long-term foreign residents develop towards Chinese culture. At the end of the book Parfitt describes how he decided to move back to Canada, finally fed up with Taiwan and Chinese society as a whole. This was clearly a long overdue decision.