I have just powered through a full-length book in Chinese. No, it wasn't the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, but a polemic by Hong Kong journalist Joe Chung. Its title, 来生不做中国人, is officially translated into English as "I don't want to be Chinese again", but a more exact rendering would be along the lines of "I won't be Chinese in my next life" or "not being Chinese in your next life" (the subject of the sentence is unstated). It has yet to be translated into English or any other language.

The book is actually a collection of the author's essays and articles. It is basically a frontal attack on Chinese culture and everything it stands for, written from the point of view of a Chinese from Hong Kong. The book's title was inspired by an opinion poll which appeared on Netease, one of China's main web portals, in 2006. The poll asked people whether they would want to be reborn as Chinese in their next life. Over the next few days thousands of Chinese took the survey, with a whopping 65% of people answering "no", until the government noticed and demanded that the poll be taken down. A Netease editor lost his job as a result.

Drawing inspiration from this episode, the author engages in a full-blown polemic against his own culture. He attacks the Chinese mindset as selfish, irrational, antiquated, petty and incapable of changing, and criticizes the Chinese people for accepting injustice by their own leaders and blaming others for their misfortunes. Unlike many Hong Kongers would do, he doesn't limit his critique to the Mainland, but criticises his native Hong Kong's culture as well, seeing in it the same flaws that hold back the whole of China.

The author dismisses Chinese culture as a culture which has long outlived its usefulness and should have disappeared long ago, and compares its survival to the Roman Empire surviving until the present day. Although he doesn't make a very big thing about it, the author is in fact a Christian, and blames the lack of a strongly held religious faith for what he perceives to be his countrymen's flawed and underdeveloped sense of morality. He claims that Confucianism is an ideology which cannot act as a substitute for true religion.

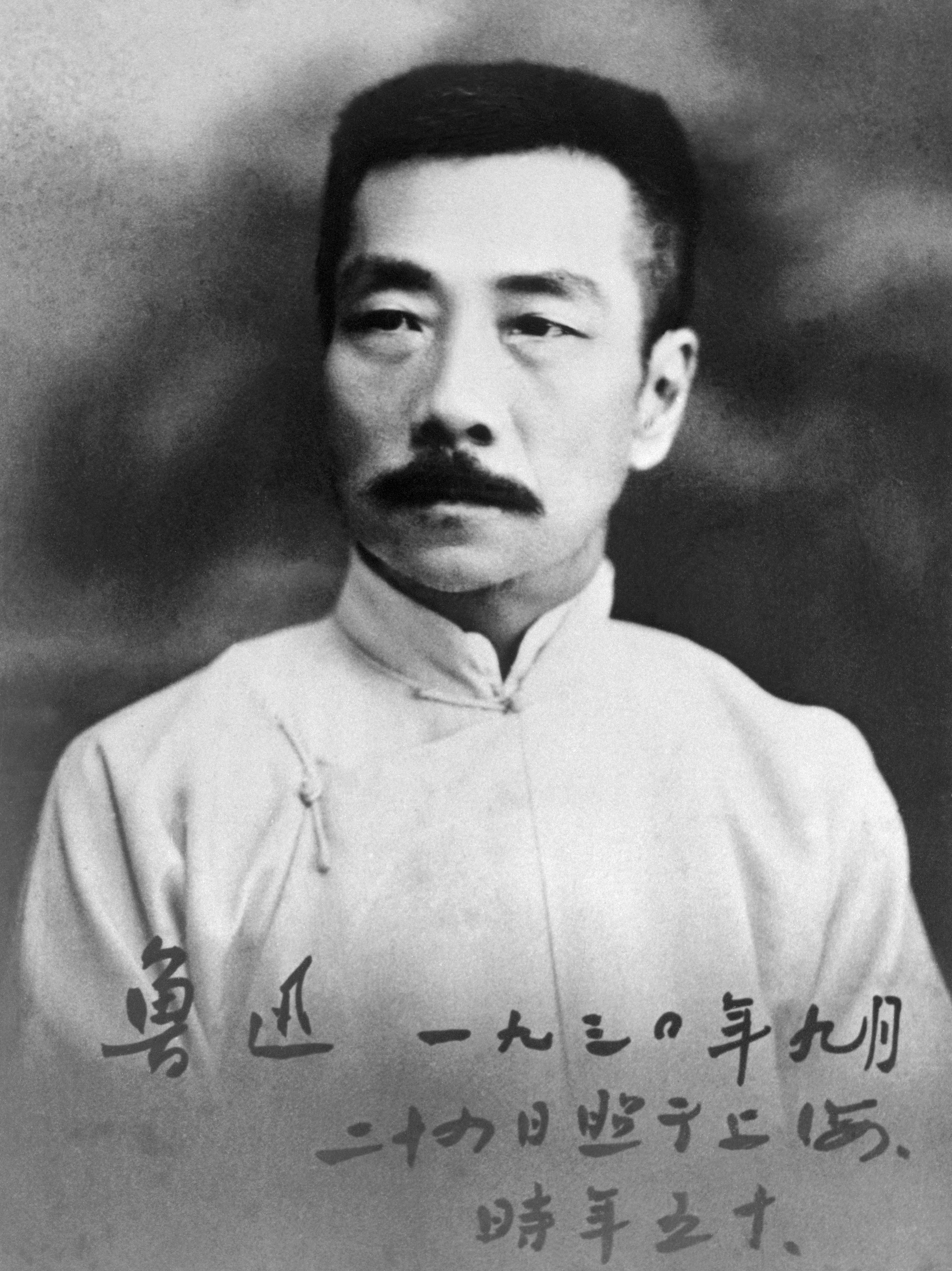

Such total dismissals of their own culture by Chinese intellectuals are actually not entirely new. A famous example is Taiwanese author Bo Yang and his well known book that came out in 1985 with the English title "the Ugly Chinaman and the crisis of Chinese culture". Under the relatively liberal atmosphere of the time, the book was actually distributed in the Mainland as well. Going back even further, China's most famous modern writer Lu Xun had some very harsh things to say about the "Chinese national character" and his own people's 劣根性 or "deep-rooted flaws". What's more he felt that the defects of the Chinese mentality had not really been improved with the Xinhai Revolution and the end of the empire. There is in fact a vein of self-hatred that has run deep within Chinese culture since at least the nineteenth century. This self-hatred actually survives in Mainland China too, although it is buried under the veneer of state-sponsored nationalism and pride.

It is certainly true that China's particular version of a modern society leaves a lot to be desired. Sometimes China can seem like a country trapped in its own history, unable to find a way out, in spite of all the economic growth and material development of the last decades. But total rejections of Chinese culture aren't really convincing either. If China's problem is the Confucian tradition and the lack of a strong religious faith, then why have the Japanese and South Koreans, who come from a similar religious and ethical tradition, been so much more successful at creating decent modern societies then the Chinese have?

Traditions and cultures all have good and bad sides. Cultures based around monotheistic religions can lead to rigidity and fanaticism, while East Asian cultures sometimes appear to lack a concept of basic moral norms that have to be abided by at all times, and lead to extreme utilitarianism and only caring about your "in-group". But the reality is that until the enlightenment took off, European societies (and other Asian ones) never appeared to be any more successful than China at producing peaceful or civilized behaviour. In fact when Marco Polo travelled around China he remarked with wonder that the men did not need to carry weapons with them when they went out, unlike in Europe at the time.

It is certainly true that China has found it harder than most countries to reconcile itself with modernity, and many progressive values which much of the modern world takes for granted still struggle to take root in China (the value of life, equality, moral concern for strangers etc...). The country's size and its isolation from "global culture", part natural and part intentional, also contribute to keep things this way. But it can only be hoped that when China finds a system that can bring out the best in its culture and people, then things will no longer be so.

The book is actually a collection of the author's essays and articles. It is basically a frontal attack on Chinese culture and everything it stands for, written from the point of view of a Chinese from Hong Kong. The book's title was inspired by an opinion poll which appeared on Netease, one of China's main web portals, in 2006. The poll asked people whether they would want to be reborn as Chinese in their next life. Over the next few days thousands of Chinese took the survey, with a whopping 65% of people answering "no", until the government noticed and demanded that the poll be taken down. A Netease editor lost his job as a result.

Drawing inspiration from this episode, the author engages in a full-blown polemic against his own culture. He attacks the Chinese mindset as selfish, irrational, antiquated, petty and incapable of changing, and criticizes the Chinese people for accepting injustice by their own leaders and blaming others for their misfortunes. Unlike many Hong Kongers would do, he doesn't limit his critique to the Mainland, but criticises his native Hong Kong's culture as well, seeing in it the same flaws that hold back the whole of China.

The author dismisses Chinese culture as a culture which has long outlived its usefulness and should have disappeared long ago, and compares its survival to the Roman Empire surviving until the present day. Although he doesn't make a very big thing about it, the author is in fact a Christian, and blames the lack of a strongly held religious faith for what he perceives to be his countrymen's flawed and underdeveloped sense of morality. He claims that Confucianism is an ideology which cannot act as a substitute for true religion.

Such total dismissals of their own culture by Chinese intellectuals are actually not entirely new. A famous example is Taiwanese author Bo Yang and his well known book that came out in 1985 with the English title "the Ugly Chinaman and the crisis of Chinese culture". Under the relatively liberal atmosphere of the time, the book was actually distributed in the Mainland as well. Going back even further, China's most famous modern writer Lu Xun had some very harsh things to say about the "Chinese national character" and his own people's 劣根性 or "deep-rooted flaws". What's more he felt that the defects of the Chinese mentality had not really been improved with the Xinhai Revolution and the end of the empire. There is in fact a vein of self-hatred that has run deep within Chinese culture since at least the nineteenth century. This self-hatred actually survives in Mainland China too, although it is buried under the veneer of state-sponsored nationalism and pride.

It is certainly true that China's particular version of a modern society leaves a lot to be desired. Sometimes China can seem like a country trapped in its own history, unable to find a way out, in spite of all the economic growth and material development of the last decades. But total rejections of Chinese culture aren't really convincing either. If China's problem is the Confucian tradition and the lack of a strong religious faith, then why have the Japanese and South Koreans, who come from a similar religious and ethical tradition, been so much more successful at creating decent modern societies then the Chinese have?

Traditions and cultures all have good and bad sides. Cultures based around monotheistic religions can lead to rigidity and fanaticism, while East Asian cultures sometimes appear to lack a concept of basic moral norms that have to be abided by at all times, and lead to extreme utilitarianism and only caring about your "in-group". But the reality is that until the enlightenment took off, European societies (and other Asian ones) never appeared to be any more successful than China at producing peaceful or civilized behaviour. In fact when Marco Polo travelled around China he remarked with wonder that the men did not need to carry weapons with them when they went out, unlike in Europe at the time.

It is certainly true that China has found it harder than most countries to reconcile itself with modernity, and many progressive values which much of the modern world takes for granted still struggle to take root in China (the value of life, equality, moral concern for strangers etc...). The country's size and its isolation from "global culture", part natural and part intentional, also contribute to keep things this way. But it can only be hoped that when China finds a system that can bring out the best in its culture and people, then things will no longer be so.

|

| Lu Xun |