During my trip to Qinghai, one of the things I found most surprising was the open display of photographs of the current Dalai Lama in all the Tibetan temples I visited.

The issue clearly remains sensitive however. In Rongwu temple I once asked a friendly Tibetan monk if one of the photos of the Dalai Lama was indeed the Dalai Lama, just to see what his reaction would be. He said it was, but he was visibly put out and uneasy about my question. The monks clearly have nothing to fear from Han Chinese visitors, however, since the vast majority of them are unable to recognize the Dalai Lama, and in any case probably wouldn’t understand what the issue was. Even my Chinese co-traveler, who considers herself to be a serious believer in Tibetan Buddhism, was unable to recognize a photo of the Dalai Lama when I pointed one out to her.

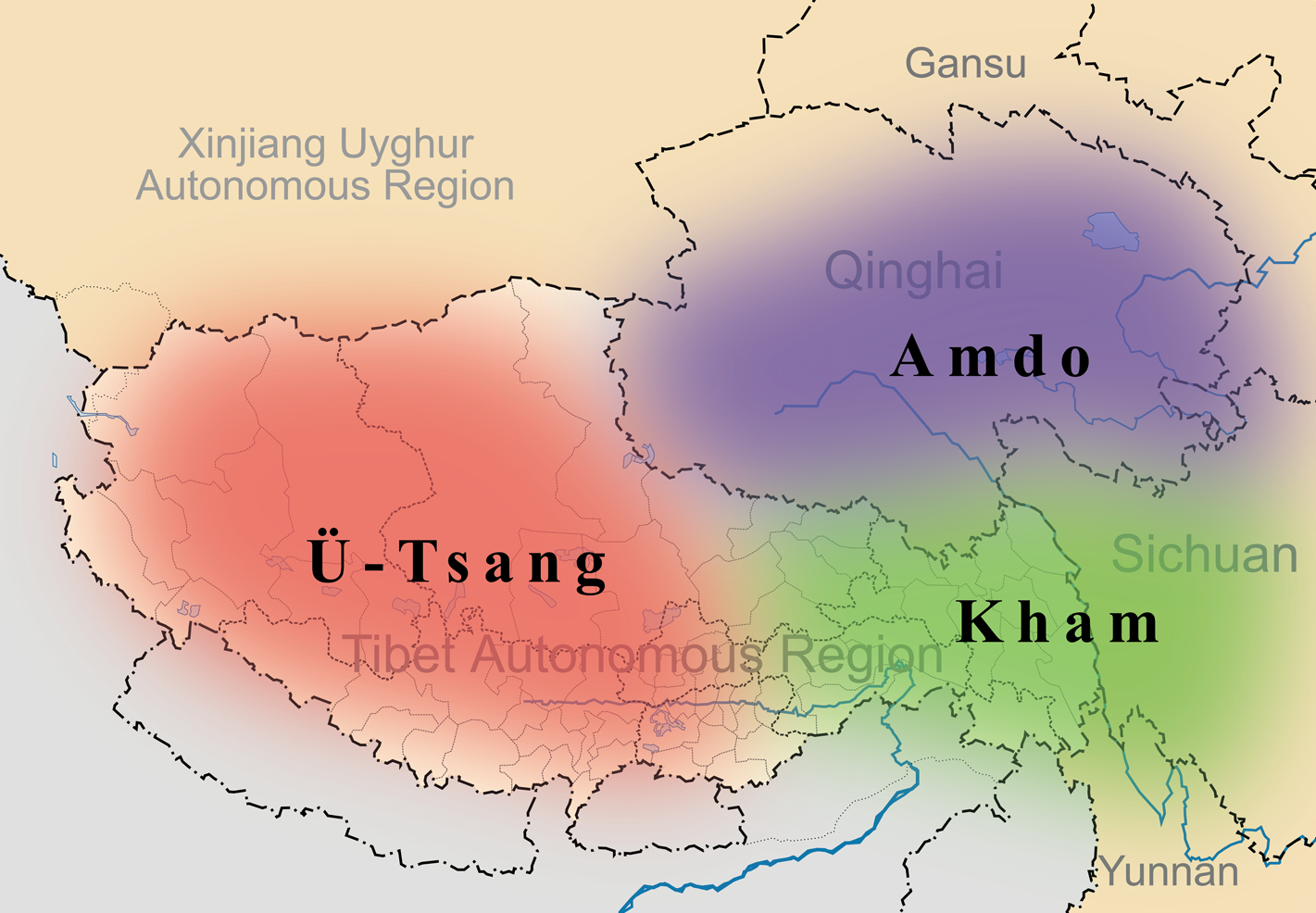

While in Qinghai I had the chance to visit the village where the current Dalai Lama was born, which is called Taktser and is situated near Xining. It is an unremarkable Tibetan village perched on the very edges of the Tibetan plateau. Then again, the Dalai Lama came from an ordinary farming family, and had an ordinary childhood until he was recognized as the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama. It is odd that the Dalai Lama’s reincarnations have always been male and Tibetan, but then the current Dalai Lama has hinted that the next one may be a woman and non-Tibetan. Although this is a great step forward, to me it just highlights the improbability of the whole belief in reincarnation to begin with.

|

| Altar to the Dalai Lama, Rongwu Temple, Qinghai |

It is often reported that publically displaying images of the Dalai Lama is forbidden in Tibet, and can lead to dire consequences. It is a verifiable fact that the Tibet branch of the official association of Chinese Buddhist of the PRC does not acknowledge the 14th Dalai Lama's spiritual authority, and that Tibetan Buddhists are officially not supposed to worship him. The Chinese government and the media constantly denounce the “Dalai clique” as a bunch of splittists and criminals.

|

| An image of the Dalai Lama in front of a statue |

All the same, every one of the Tibetan temples I visited had images of the 14th Dalai Lama in prominent display in front of their altars, next to photos of the Panchen Lama and of other important Lamas. When I had the chance to witness a large group of monks chanting sutras in Rongwu temple, like I describe in this previous entry, there was a large picture of the Dalai Lama hanging on the wall above them. I have heard that such photos are taken down if there is an official inspection of the monastery, but I obviously had no way of witnessing this.

The issue clearly remains sensitive however. In Rongwu temple I once asked a friendly Tibetan monk if one of the photos of the Dalai Lama was indeed the Dalai Lama, just to see what his reaction would be. He said it was, but he was visibly put out and uneasy about my question. The monks clearly have nothing to fear from Han Chinese visitors, however, since the vast majority of them are unable to recognize the Dalai Lama, and in any case probably wouldn’t understand what the issue was. Even my Chinese co-traveler, who considers herself to be a serious believer in Tibetan Buddhism, was unable to recognize a photo of the Dalai Lama when I pointed one out to her.

While in Qinghai I had the chance to visit the village where the current Dalai Lama was born, which is called Taktser and is situated near Xining. It is an unremarkable Tibetan village perched on the very edges of the Tibetan plateau. Then again, the Dalai Lama came from an ordinary farming family, and had an ordinary childhood until he was recognized as the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama. It is odd that the Dalai Lama’s reincarnations have always been male and Tibetan, but then the current Dalai Lama has hinted that the next one may be a woman and non-Tibetan. Although this is a great step forward, to me it just highlights the improbability of the whole belief in reincarnation to begin with.

|

| The Dalai Lama's place of birth, Taktser, as it appeared on our arrival |

To get to the village we took a taxi from the nearby town of Ping’an. The taxi wove down winding mountain roads until it reached Taktser. When we arrived, the driver pointed out a house with an impressive entrance, which he informed us is the house where the Dalai was born. Surprisingly the house has been restructured, and it has an exhibition inside which is open to visitors. However, my guidebook warns that during periods of tension in Tibet foreigners may not be allowed in. I soon found out that this was one of those times.

My friend and I entered the home, since there was nobody to stop us, and reached a small courtyard with a large Tibetan prayer mast which I had the time to photograph. As soon as I had done so, a group of men on the second floor saw me and gestured brusquely for me to leave. One of them was in uniform, and they were clearly responsible for security. I wasted no time in leaving and going back to the taxi.

In the meantime, my friend attempted to argue that as a Chinese she should be allowed in, but they told her that she couldn’t because she was accompanying a foreigner. If she came back on her own the next day, they would let her in. To top it, they told my driver not to bring any more foreigners to the village. We then noticed that there were cameras placed at the house’s entrance.

Although I didn’t get the chance to see the exhibition inside the house, I suspect that it downplays the whole dispute there is between the Chinese government and the Dalai Lama, or even completely ignores it. As we left I reflected on how surprising it is that the authorities should have opened up the Dalai Lama’s ancestral home to visitors, and how sadly predictable it is that they should have this sort of reaction when a foreigner comes to have a look.

|

| Here I am about to enter the house where the Dalai Lama was born |