Tibet is one of those places which many people fantasize about, many others have strong opinions about, but few have actually visited or understand.

The whole of the Tibetan plateau is a vast region, which covers an area practically the size of Western Europe, but the harsh climate and conditions ensure that it remains scarcely populated. The scarce population, limited economy and unwelcoming geography means that few people actually have the need or possibility to go there, while its unusual religious traditions and inaccessibility have fueled a tendency to romanticize this remote place and its people. This is not just a Western thing: even the modern Chinese have a certain tendency to view Tibet as a romantic land of mystery and legend, although they may not extend this attitude towards Tibetans they actually meet in real life.

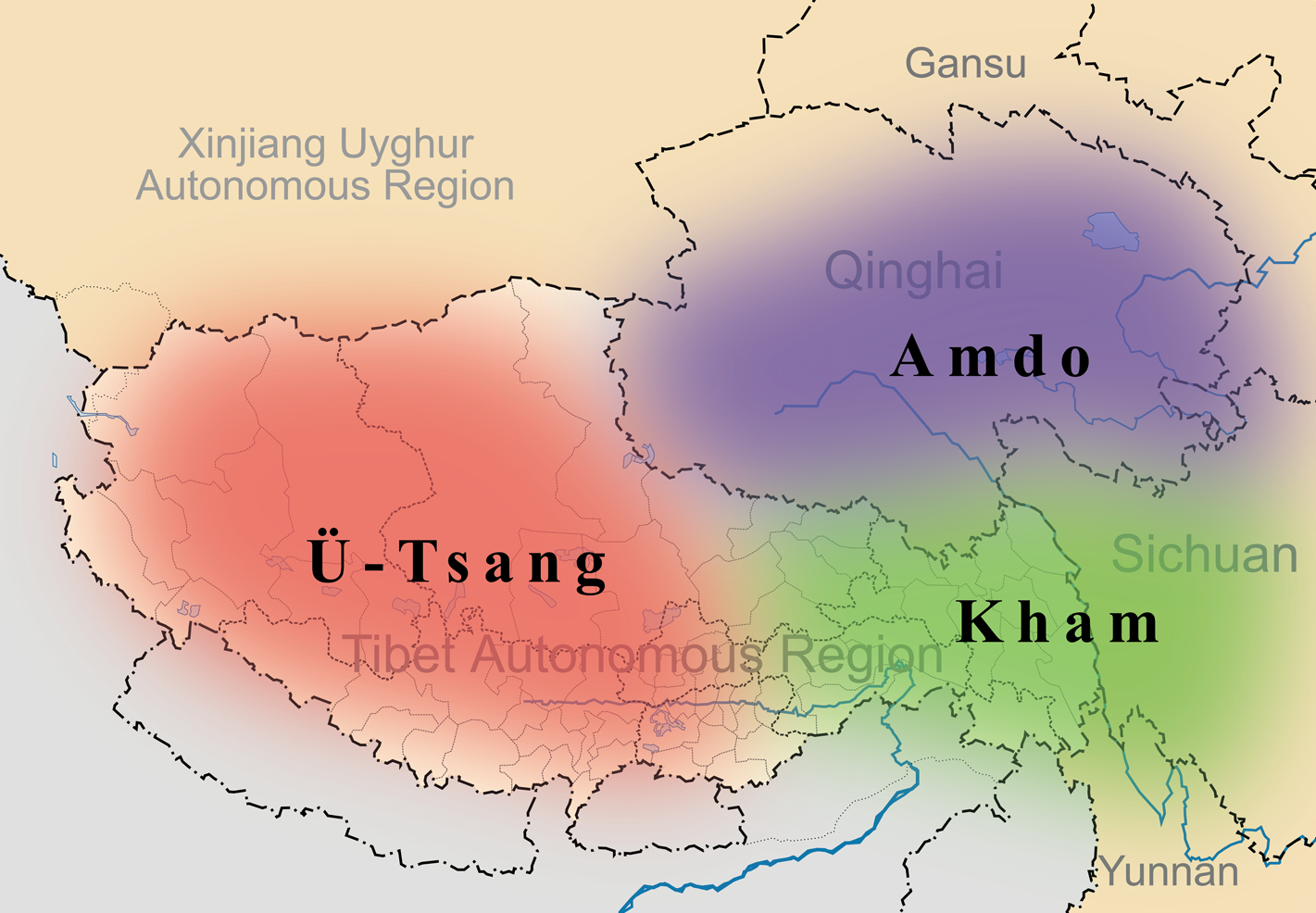

Since moving to China I had always wanted to go and see Tibet, but had never had the chance. Then recently I finally saw the opportunity to take a week off work and go and explore the region. There is only one problem: The Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), the official province of Tibet on Chinese maps, is closed off to individual travel by foreigners. You are only allowed to go there by joining a tour or hiring a guide, which is expensive and limits your freedom. The TAR, however, does not comprise the whole of historical Tibet. The nearby province of Qinghai and the West of Sichuan province also lie in the Tibetan plateau, and are culturally part of the Tibetan world.

Because of the impossibility of going to the TAR alone, I opted for Qinghai instead. This province is itself bigger than any European country, but it only holds five million residents. It corresponds roughly with the old Tibetan province of Amdo. Currently only 21% of the population is actually Tibetan, while 54% are Han Chinese and the rest are mostly Hui Muslims or belong to other minorities.

Having said that, most of the Han and the other minorities live in the capital Xining and in the surrounding Eastern tip of the province. The vast Western and Southern expanses of Qinghai are inhabited mostly by Tibetans, and form very much a part of the Tibetan world. This is officially recognized too, since five of the province’s eight prefectures are designated as “Tibetan autonomous prefectures” and one as a mixed “Tibetan and Mongol autonomous prefecture”, following the Chinese system of autonomy for minorities.

Having said that, most of the Han and the other minorities live in the capital Xining and in the surrounding Eastern tip of the province. The vast Western and Southern expanses of Qinghai are inhabited mostly by Tibetans, and form very much a part of the Tibetan world. This is officially recognized too, since five of the province’s eight prefectures are designated as “Tibetan autonomous prefectures” and one as a mixed “Tibetan and Mongol autonomous prefecture”, following the Chinese system of autonomy for minorities.

It must be pointed out that the Tibetans in Qinghai have not really been ruled from Lhasa since the break up of the great Tibetan empire of the 7th-9th century. This empire spread all the way to what is now Bangladesh and at one point actually occupied the Chinese capital of Chang’An, as amazing as it may seem nowadays.

Since that empire broke up, Amdo was ruled mostly by local chieftains who sometimes pledged allegiance to the Chinese empire or to Lhasa, but enjoyed basic autonomy. The Tibetans who live there now speak a dialect of Tibetan which is not mutually intelligible with the dialect spoken in Lhasa and Tibet proper, and are relatively more integrated into mainstream Chinese culture.

Since that empire broke up, Amdo was ruled mostly by local chieftains who sometimes pledged allegiance to the Chinese empire or to Lhasa, but enjoyed basic autonomy. The Tibetans who live there now speak a dialect of Tibetan which is not mutually intelligible with the dialect spoken in Lhasa and Tibet proper, and are relatively more integrated into mainstream Chinese culture.

A map showing the three traditional regions of Tibet, and how they fit into the modern Chinese provinces of Tibet, Qinghai and Sichuan.

How do I feel about the political dispute over Tibet? The Chinese claim that Tibet is historically part of China seems to me not exactly unassailable: it is based on the fact that Tibet was ruled by the Chinese Yuan and Qing dynasties, while for the rest of history it was basically independent, although of course it always had strong links to the Chinese world. Even during periods of Chinese rule Tibet had a lot of autonomy in practice, and the Chinese presence was not very heavy. Even so, the Chinese seem to base their territorial claims on the shape China had during its last dynasty, the Qing dynasty which was broken up by European invaders. In that period, Tibet was indeed under Beijing's rule.

For what the Chinese are concerned, it was the European invaders who took Tibet away from them, and they were just taking back what was theirs in 1951. They view Western support for Tibetan separatists as a way of undermining China’s rise, and extremely few Chinese are at all open to the idea that their might be anything legitimate to the Tibetans’ national aspirations. Educated to think of China as a multiethnic country with 56 different peoples forming one nation, they cannot see how the Tibetans might not feel that they fit into that picture.

The Chinese also assert that they have brought great improvement to the lives of ordinary Tibetans, and that the social system which existed in Tibet under the Dalai Lama was backward, theocratic and inhumane. There is certainly substance to these claims, and I don’t doubt that an independent Tibet would hardly be a prosperous country. Neighbouring Nepal is quite a lot poorer after all. The Chinese have built significant infrastructure and brought much modernization.

Pre-1951 Tibet was certainly a backward theocracy in great need of reform (although not the hellhole which the Chinese government portrays it to have been). At the same time I can see how Tibetans might have rather had reform without the full scale attack on their culture carried out under the Cultural Revolution, the repression of any expression of their grievances, and what they see as another people ruling over them even today.

The Chinese claim that the Tibetans, just like other minorities, are allowed certain privileges under Chinese policy, and that Tibetan areas have already been granted autonomy. It is true that the Tibetans don’t have to follow the one child policy, and have special places reserved in university. It is also true that their language does enjoy a certain degree of official recognition and protection, as I saw for myself in Qinghai.

On the other hand, Tibet’s autonomy in government seems to be quite symbolical, and while the governor of the TAR is always Tibetan, the far more powerful Party Chief of the province is always a Han Chinese. While claims by the exiled opposition and their Western supporters about a full scale attempt to destroy Tibet’s culture by flooding the region with Chinese migrants are rather exaggerated (only 8% of the TAR’s population is non-Tibetan right now), there is clearly much genuine and legitimate resentment against Beijing rule amongst Tibetans.